Posttraumatic stress fundamentally challenges

the notion that time can heal all wounds.

– David Treleaven –

Over thirty years ago, my mindfulness journey officially began when I took my seat on a meditation cushion during my sophomore year of college. Initially, I found a great deal of peace through meditation. For the first time in my messy, early-adult life, I felt a sense of grounding and “at-homeness” that I had been seeking outside of myself throughout much of my existence. Honestly, it was often a bit surprising to discover that my need for a sense of calm and balance could be found inside myself because I’d rarely felt “at home” inside my own body.

In the midst of these positive experiences, I can also recall moments of feeling overwhelmed and extremely agitated while meditating. I could best describe these overly challenging moments as prolonged feelings of wanting to crawl out of my own skin. What I didn’t understand then, that I understand today is I was experiencing a trauma response likely brought on by the very thing that had brought me so many moments of peace—my meditation practice.

Unfortunately, at the time, I didn’t know what Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) was, nor did I recognize I was suffering from Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD). And even if I had, resources for mindfulness practitioners who had experienced adverse reactions while practicing meditation were virtually nonexistent.

Mindfulness and meditation teachers were also often significantly under-educated and under-resourced in ways to support people with these types of experiences. Some teachers even believed that feelings of extreme discomfort during meditation were positive signs of spiritual growth. Personally, I have a distinct memory of sharing with a meditation teacher about the distress I was feeling during practice, and in response received his assurances that I was simply “sitting in the fire of purification”. He suggested the best thing I could do for myself was to continue to sit with the discomfort until it shifted. Perhaps that seemed like wise advice at the time, but it definitely created moments of white-knuckling my way through meditation practice.

The Mixed Blessing of Mindfulness

Mindfulness, and its formal meditation practices, can have both positive and negative effects on someone with a trauma history. On the one hand, through the cultivation of mindfulness, a practitioner can improve their capacities to both direct and sustain attention providing a valuable resource for choice and greater self-agency. Additionally, the cultivation of nonjudgmental awareness can develop a practitioner’s capacity to decenter from experiences, allowing them to witness thoughts, emotions, and bodily sensations from a more objective rather than subjective vantage point. Both of these benefits of mindfulness can foster the skill of self-regulation—something trauma survivors often struggle to manage and maintain.

On the flip side of that same coin, however, meditation practices can also trigger nervous system dysregulation. Trauma survivors are often haunted by their trauma, sometimes experiencing obtrusive thoughts, overwhelming physical sensations, and flashbacks to memories of traumatic events. Mindful awareness can bring these experiences into greater focus for trauma survivors, potentially flooding them with feelings of overwhelm and triggering the autonomic nervous system’s fight, flight, or freeze responses.

Understanding the Window of Tolerance

As a certified teacher of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and advanced practitioner of Trauma-Sensitive Mindfulness, one tool I introduce to new mindfulness practitioners, whether they identify as a trauma survivor or not, is the concept of the Window of Tolerance.1

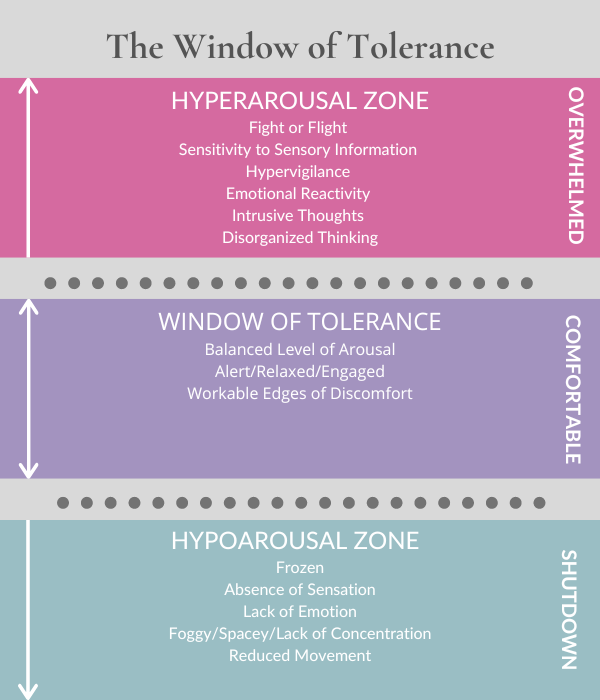

The framework of the Window of Tolerance addresses ranges of nervous system activation and their impact on how we experience the mind, body, and emotional states. Arousal activates the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) to varying degrees, helping us to respond to perceived demands. When we are experiencing a balanced range of arousal we feel alert, relaxed, and engaged. Although we may experience edges of increased or decreased arousal, these edges are held within a perceived range of manageability. In these moments we are within our Window of Tolerance.

When there is too much arousal, however, we can move into a state of hyperarousal, whereby the sympathetic branch of the ANS is activated and the alarm of the fight or flight system becomes activated. In this state, we may find ourselves feeling physically agitated, overloaded by sensory sensations, experiencing intrusive and repetitive thoughts, disorganized thinking, and a heightened state of anxiety. In short, there is a sense of being overwhelmed.

In the instance of too little arousal, which can sometimes occur after prolonged states of activation of the fight or flight response, the parasympathetic branch of the ANS is activated and the freeze response kicks in. In this state, we may experience feelings of numbness, both in terms of sensory experience and emotion. We may feel listless in our bodies and foggy or spacey in our thinking. Ultimately, we experience a sense of energetic shutdown in the body.

These thresholds of arousal between the Window of Tolerance, fight or flight, and freeze, can vary from person to person and even from situation to situation for each individual. In the case of people who’ve experienced trauma, their Window of Tolerance can be extremely limited. They can also move from a balanced state of arousal (self-regulated) to dysregulated states of arousal fairly quickly.

This conceptual framework of the Window of Tolerance can provide meditation practitioners with a self-monitoring tool to gauge their level of arousal from moment-to-moment as they meditate, and if they find it necessary, adjust their practice to support a greater sense of safety and manageability. Additionally, as people work with the Window of Tolerance over time, they can begin to recognize their personal triggers and even begin to widen their Window of Tolerance to withstand discomfort. This can be especially helpful when people are working to integrate a trauma history.

Whether you are an experienced mindfulness practitioner, new to practice, or considering learning the practices and principles of mindfulness, if you find yourself having any of the adverse experiences described above during meditation, and potentially for significant periods of time afterward, it is important to understand that you may be having a trauma response. The guidance of a trained, trauma-sensitive mindfulness teacher may help you to identify modifications you might consider making to support yourself during formal practice time.

Meeting Trauma on the Meditation Cushion

I speak from experience when I say that practicing mindfulness and meditation can be powerful allies throughout the healing journey. The caveat for trauma survivors to keep in mind, however, is the directing of attention toward internal experiences that are often encouraged during formal meditation can also trigger the dysregulation of the nervous system. This can move practitioners out of their Window of Tolerance and into states of overwhelm or shutdown.

Understanding the Window of Tolerance and how levels of nervous system activation can be experienced in the body, heart, and mind, is an essential tool for trauma survivors to become familiar with so they are able to monitor for, and potentially address, dysregulation during meditation practice. Over time, this self-monitoring tool can facilitate a widening of the Window of Tolerance, both on the meditation cushion and off.

If you’d like to learn more about the practices and principles of mindfulness in a trauma-sensitive environment, check out our upcoming Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) courses for opportunities to learn and grow.

Already have an existing practice? Consider joining us for ongoing practice opportunities.

- Siegel DJ. (1999) The Developing Mind. New York: Guilford.

↩︎

The Healing Waters of Loving-Kindness

The Healing Waters of Loving-Kindness